LAS VEGAS REVIEW-JOURNAL

You know you love your stuff when you buy furniture for it.

Before he acquired an IKEA shelf in 2008, Brett Kasden kept his roughly 250 record albums in milk crates. But after a years’ long love affair with vinyl, he thought it was time to display them in a more respectable and visible way. After all, he loves his stuff.

“I consider myself a casual collector,” says Kasden, 27. “I put very little time into it, but I guess I take it seriously enough that I bought a shelf specifically for my albums. That’s kind of funny.”

Stuff: It can be anything. And it can be absolutely nothing. However it’s defined — material, substance, essence, even worthless objects — Americans seemingly can’t live without it. Nor can they stop acquiring it.

Take Apple’s launch of the iPad 2 on March 11. Thousands of people stood in line for hours hoping to be among the lucky few to buy the latest, greatest thing since last year, when the original iPad came out.

It has become a common sight in this country. Around the holidays or whenever a new product hits store shelves, Americans line up to buy more stuff.

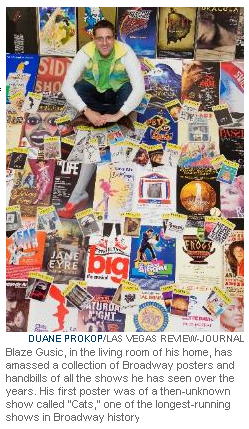

“I do think Americans are defined by material possessions, sadly. And I ask myself all the time, why do things have such importance in our lives?” says Blaze Gusic, 45, a local pediatrician who collects Broadway handbills and posters.

Mohandas Gandhi, who supposedly could fit all of his worldly possessions into a shoe box, might wonder the same thing. But rest assured, there is a valid reason behind our drive to acquire and then acquire some more. And a reason why we have such a hard time parting with our stuff. At least, a valid American reason.

Research has shown that material possessions have become an extension of ourselves, says Angeline Close, a professor of marketing at the University of Nevada, Las Vegas. So essentially, the stuff we have defines who we are. Or who we think we are and want to be.

“It’s called extension of the self, but really it’s extending the perceived self,” says Close, who studies consumer behavior. “For instance, if you perceive yourself as someone who is adventurous, you might be attracted more to something that is perceived as an adventurous brand, maybe something rugged or outdoors-related.”

As for all those enthusiastic Apple fans who stood in line to be among the first to own an iPad 2, they are the rarest of consumers: the hip and cool. The trendsetter. The tech savvy. Only about 13 percent of consumers are believed to be among those who must be the first to own something, Close says. But they’re still using the iPad 2 to define themselves.

“They benefit from a sense of satisfaction of being the first,” Close says. “But it can backfire because when something new comes out, it’s usually better to wait a bit for the kinks to get worked out. These first people are also risk takers in the sense that they don’t wait for the company to tweak the product.”

How you see yourself influences the things you buy and the possessions you value most. So it’s not surprising that consumer consumption is emotionally driven and even influenced by the people in our lives. Researchers have found that pleasure seeking centers in the brain are heightened when people buy stuff.

“Consumers don’t have the ability to step back and see underlying reasons or motivations for why we buy material goods. It’s shaped by culture, your family, your subculture. There’s evidence to suggest that your peer group strongly influences your buying behavior,” Close says. “Advertisers know this.”

When local Lori Nelson, 40, was a kid, her parents took her to see “Annie” on Broadway. That experience sparked a lifelong interest in live theater and music; to date, Nelson has seen dozens of plays, concerts and sporting events. About 25 years ago, she started saving the ticket stubs to every live event she attended. They serve as a tangible reminder of the good feelings she experienced at that time.

“Theater was something I was introduced to as a child by my mom,” Nelson recalls. “We were a middle class family, so going to a live event was a very special experience. And when I go, it’s not unusual for a play or concert to evoke strong emotions. So for me, (the stubs) are very personal.”

The antithesis of a collector, Nelson possesses an anti-collection of ticket stubs from George Michael concerts, Debbie Gibson performances and others. She decided on a whim to see what would happen if she started saving them.

“I thought this would be a really fun, nostalgic thing to document what I’ve done because sometimes you lose track of time, don’t remember when or where you were when you experienced something,” Nelson says.

Even though she stores them in a giant envelope and doesn’t look at them on a daily basis, Nelson wouldn’t want to part with them.

“I’ve never thought about that. I’d say giving them up would take a little piece of me away,” Nelson says. “I can replace a TV or a couch. But these tickets, to me, are my documentation of some important things I’ve done along the way.”

There is a common sense reason why people have a hard time getting rid of things, Close says. It’s because there’s a memory attached to something, even if it’s torn or stained or unusable.

However, the opposite also is true; when there’s a bad memory attached, people usually don’t have trouble parting with something.

Kasden can’t imagine losing an album, mostly because he would have to buy another one. But his collection also is a part of his identity. And it’s uniquely his.

Not surprising that he feels that way; Americans above any culture value individualism, Close says.

“When I first started collecting, it was fun, like discovering an entirely new world of things,” says Kasden, who prefers punk rock music. “No one in my family was into stuff like that so it seemed like something entirely my own.”